Tag: cancer

How can we really understand informed consent?

April 3, 2011 GUEST BLOG POST by Aimee Hilton

You are told you have a left clavicle contusion and your face just screams “What?” You go home to research and find you simply have a bruised collarbone, i.e your shoulder is going to hurt for a little while. Doctors may forget that they spent eight plus years in education learning the medical jargon that most of their patients do not understand. So when the patient has an important decision on the line, like whether or not to participate in a clinical trial based on their illness, how do we organize the information to make an informed decision? When we can’t understand words like randomization and placebo, how can we really understand the informed consent?

You are told you have a left clavicle contusion and your face just screams “What?” You go home to research and find you simply have a bruised collarbone, i.e your shoulder is going to hurt for a little while. Doctors may forget that they spent eight plus years in education learning the medical jargon that most of their patients do not understand. So when the patient has an important decision on the line, like whether or not to participate in a clinical trial based on their illness, how do we organize the information to make an informed decision? When we can’t understand words like randomization and placebo, how can we really understand the informed consent?

A study performed by Jefford et al. (2009), looked at how well patients understood the clinical trial they recently enrolled in. 102 patients who signed up for a clinical trial concerning cancer within the last two weeks participated in the research. The most important results showed that doctors needed to ask specific questions pertaining to the patient’s understanding of the trial, instead of simply “Do you understand”. Using a method known as “the teach back method” allows the patient to understand and develop questions. As a patient, if making a decision about a clinical trial, be sure to restate the clinical trial process and informed consent to your doctor. It will make sure you understand and they know you understand.

Patients should also receive written information and a recording of the conversation discussing the clinical trial. This allows the patient to go back and look over any information they found confusing or did not comprehend. Doctors also should be sure to discuss the standard treatment and other possible treatments in the trial. Patients should be aware of all options and possibilities throughout the trial.

It may seem that clinical trial information is overwhelming. However, if the doctor presents the information in an organized process, the patient will be more likely to understand and receive enough information to understand the informed consent they need to sign. Clinical trials are very important for the advancement of science and treatments. If doctors can help patients have a better understanding of the trial, hopefully more patients will be willing to participate.

Jefford, M. Mileshkin, L. Matthews J. et al. Satisfaction with the decision to participate in cancer clinical trials is high, but understanding is a problem. (2009) Support Care Cancer, 19, 371-379.

What did Dr. Oz say about genes and health, and what did his guest doctor say about viruses causing cancer that left me talking to the TV–and not in a happy voice?

February 4, 2011

Aieeeeeeeee. Dr. Oz had some visiting doctors on his show again today. As they were wrapping up some of the discussion, Dr. Oz said, “Genes load the gun… The environment pulls the trigger… I want you to remember that.” What?! We have discussed the importance of family health history in this forum before. So the role of genetics is one that is an important topic when talking about health.

Aieeeeeeeee. Dr. Oz had some visiting doctors on his show again today. As they were wrapping up some of the discussion, Dr. Oz said, “Genes load the gun… The environment pulls the trigger… I want you to remember that.” What?! We have discussed the importance of family health history in this forum before. So the role of genetics is one that is an important topic when talking about health.

But I wonder how many viewers really got the idea that it was family health history they should be thinking about with his expression–“Genes load the gun.” This is an old metaphor for the role of genes for health and has not been very effective. Add to that, the conversation that Dr. Oz was having about genetic mutations on the show. It all got mushed together…

“The environment pulls the trigger.. I want you to remember that.” Really? What does it mean? Again, the meaning of environment in this metaphor has many interpretations. Environment for most people is about where they live, the climate, the neighborhood, pollution… those things all matter when it comes to our health and interact with our family health history. But environment includes our personal behavior and our social environment–friends, family, and culture. What we eat, for example, is part of the ‘environment’ that our genes live in… But I am not confident that this meaning is clear when talking about genes and health with this metaphor…

Then there was the conversation about viruses–that cause cancer. HPV was one of the two examples discussed. I think that this also was not a good way to discuss the issue. If I have cervical cancer, you cannot ‘catch’ it from me. Cervical cancer is not a virus that can be passed from one woman to another. Cervical cancer is often caused by the lesions that form from genital warts caused by HPV–the humanpapilloma virus. So there is a virus that causes a condition that may be the cause of cancer…and not just cervical cancer but also penile cancer and throat cancer and head and neck cancers… So we may pass a virus between us that leads to genital warts that sometimes do not heal and may cause some changes in our cells and become cancer…

Then there was the conversation about viruses–that cause cancer. HPV was one of the two examples discussed. I think that this also was not a good way to discuss the issue. If I have cervical cancer, you cannot ‘catch’ it from me. Cervical cancer is not a virus that can be passed from one woman to another. Cervical cancer is often caused by the lesions that form from genital warts caused by HPV–the humanpapilloma virus. So there is a virus that causes a condition that may be the cause of cancer…and not just cervical cancer but also penile cancer and throat cancer and head and neck cancers… So we may pass a virus between us that leads to genital warts that sometimes do not heal and may cause some changes in our cells and become cancer…

So let’s focus on understanding that increases our health literacy and not shorthand expressions that don’t… And let’s look toward spring and the daffodils that will replace the frozen icy tundra in my woods today…

Do we want doctors to tell us if we have advanced cancer?

February 18, 2010

February 18, 2010

In 2002, Hisako Kakai published an article in the journal, Health Communication, about preferences for disclosure of a cancer diagnosis. Dr. Kakai indicates that in Japan, a direct communication style is usually preferred when it comes to disclosing one’s personal diagnosis of cancer. In other words, people want to be told they have cancer. However, an indirect communication style with no disclosure, or an ambiguous disclosure to the patient was preferred for a family member. The article raises many interesting communication and ethical issues.

A serious diagnosis raises the question, ‘how do we deal with uncertainty?’ Communication plays a big role. It points to the reality that we often are not good with dealing with uncertainty. We frame uncertainty as ‘bad’ and let uncertainty overtake everything good that might be going on in our lives. This relates to how we communicate about a serious health condition. It also relates to how we communicate about the economy, about security, and about an endless number of issues that equal being — human.

The message communicated often to us is, ‘work hard and it will pay off’ — with payoff crossing a spectrum from health, relationships, and wealth. The message, ‘life is uncertain. Work hard at your relationships and school and work, and take satisfaction in the fact that you worked hard’ — is communicated less often, if at all. And it shows up in our inability to deal with uncertainty, our obsession with …reducing the uncertainty.

Should the goal in communicating be to reduce uncertainty? When it comes to our health, that may not always be the best aim. If we can learn to manage the uncertainty of a diagnosis, we may be better able to live our lifes as someone living with cancer or heart disease or diabetes. If we make the diagnosis a more integral part of our being and identity, we may communicate in ways that define us to others as being disabled rather than living with a disability, diabetic rather than managing life while living with diabetes, and so on.

Even more surprising, when we focus on managing our uncertainty as a part of life, we may even discover that there are times when we communicate to increase uncertainty. Instead of being certain that our future, our health, our well-being are uncertain and that is a bad thing, we can use uncertainty as a way to promote hope. In our own research, Ben Cairns and I found that this was particularly important for people who have newly experienced spinal cord injuries and their family members. ‘Will she walk again? Will he be able to do things for himself? Can she sit up on her own? Can he feed himself?’ Not knowing offers people living with the injury and their families and friends the hope that they might do these things again.

Communicating to increase uncertainty about a diagnosis thus gives some time to adapt to a diagnosis. And that may be the best and more ethical way to communicate about an advanced cancer diagnosis as well. Not telling so that a patient does not know a true diagnosis may seem to offer a way to manage a serious diagnosis and thus to reduce uncertainty. Telling and acknowledging that the diagnosis is serious, even very serious, but that predicting exactly when the end-of-life will happen is uncertain may give some time to adapt to the diagnosis and some hope that important things that have not been said can be…

…a lesson in Dr. Maureen Keeley’s award-winning book, Final Conversations that has been shown to be so important for those who know that they are dying and the loved ones they will leave behind.

Why should you talk about family history and health?

January 12, 2010

January 12, 2010

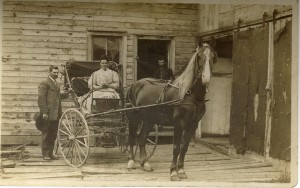

The woman on the horse is a relative that I share a first name with…tho, of course, I never knew her. I wonder what else we might share. Hair color, height, health?

The U.S. Surgeon General advises us to ‘know our family health history.’ The problem is, what to know and how to know it. Since 2004, the Surgeon General has declared Thanksgiving to be National Family History Day [http://www.hhs.gov/familyhistory/] as part of an initiative to get us talking. While we do need to find a time to talk with our family about our health histories, few things seem more doomed to failure than pushing families to talk about poor health at a gathering aimed at celebrating.

First, older adults in our families have many interesting things to tell us about that go on in their lives besides poor health. Many have good health and no reason to focus on poor health. Many want to avoid the stereotype linked to old folks talking about their health and nothing else…even when they do have poor health.

Second, younger adults who need to know about their family health history need to know details that are unlikely to be discussed in such public settings, or if they are discussed, unlikely to be remembered.

Third, it is not particularly helpful to know that there is diabetes or heart disease or cancer in your family if you don’t also know who had the condition, at what age they had the condition, what treatment they used to address the condition, and with what success. Or, knowing what family members have died from should be accompanied by information about the age at time of death.

In this era when we have more awareness of how genes affect health and our reponses to medications and other therapies, we may want to know whether our family members have had any genetic tests. If they have, what ones led to positive results indicating the presence of a particular form of a gene?

Talking about family health history is important but can be difficult if we don’t make time and don’t know what to talk about….

What about public health care reform?

January 10, 2010

January 10, 2010

I never hear anyone talk about public health when they talk about ‘health care reform.’ This bothers me because we have a univeral system of public health in the U.S. and we spend quite a lot of resources on it. The services linked to our public health care system range from checking the quality of restaurants and ‘grading’ them to providing newborn screenings. We spend quite a lot of time deciding what services to provide in each state. Besides registering births and deaths, and newborn screenings, many states have prenatal care programs, other women’s health programs, and a wide range of programs from smoking cessation to drug prevention to cancer screenings.

We don’t talk much about public health. But what might a connected system of health care built on the system of clinics and services for public health look like? How would doctors and health care staff feel about building on their infrastructure? Some states have regional health care directors? How would they regard an effort to connect the services they oversee to a broader range of services for the public to consider as a choice for care?

Anyone?

How much “chemo” is too much or too little?

January 3, 2010

January 3, 2010

It doesn’t surprise us to think about needing different dosages of medications…pain relievers, aspirin, and so on. But how often have you heard anyone talk about the dosage for chemotherapy?

My good friend will begin chemotherapy for her colon cancer in a couple of weeks. She was reading a bit online about some of the research related to the treatment. She read that obesity may make it difficult to determine the right dosage for someone’s chemotherapy to be enough to work. Not that she is fat. Quite the opposite. She is a petite woman of average weight. So she wonders if perhaps she needs a lower dose of chemo to work but to avoid some of the toxicity that a so called average dose would have for her. She will ask her oncologist about it.

Another example of important work being done in cancer research studies to help patients get the most out of their treatment. It would be awful to go through chemo and have it not work because you were overweight and didn’t get a high enough dosage…

Another example, too, of how the ‘normal’ dosage is not a one size fits all prescription. A good lesson to keep in mind when we talk about health…our size and the dosage we need.